Ai Weiwei’s exhibition at the Royal Academy is high on spectacle and easy to enjoy, though you might find yourself wondering how certain things in it ever got taken seriously. He’s a juggernaut artist, steamrolling across the world with constant shows and noisy publicity. He’s known for his head-banging amazing bravery in provoking and standing up to the Chinese government. But in this country, at least, his notoriety as a figure hasn’t been matched until now by knowledge of his art. Here the balance is corrected.

This survey represents work made over a period of 22 years, accompanied by a catalogue with brief light essays and an interview. You quickly gain an impression of what he’s about. Art as destruction, art as readymade object, a flow between art and life, and the freedom for art to be made of any materials and to have any meaning an individual artist wants.

The results are not as great as the ideal sounds, if in fact it really does sound all that great. It’s a romantic vision of art that many people who aren’t artists have, leaving out the making side and emphasising vision and specialness instead, or a specialness that is unaccountable and ineffable.

Ai himself is subject matter for his art but distanced from his real self, made into an icon of freedom and a hero of civil rights. And ordinary things in the world become subjects, too, with their ordinariness made peculiar — with predictable results. The predictability is misunderstood by Ai as democracy and accessibility. But looking at his stuff you’re often confronted by a misfit between concept and making that causes created objects to be visually dull or lacking an intrinsic visual reason to exist. A marble pram is placed on a bed of marble grass with neither object having any features that really connect. A hexagonal shape in one fails to chime with a square shape in the other: heights in each are arbitrarily different.

It becomes a serious problem when a sculpture seems to be a decorative thing standing alongside a concept rather than embodying it. I’m thinking of the exhibition showpiece entitled Straight. This is an installation made of metal rods salvaged from the rubble of school buildings destroyed in the 2008 Sichuan earthquake that caused more than 5,000 deaths.

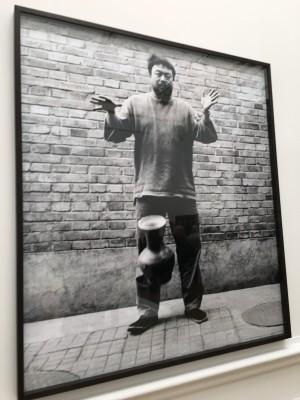

Sadly, sometimes he seems like a nit. He has purchased innumerable antique pots over the years, originally crafted during periods ranging from the early 20th century to prehistory, which he’s dipped in industrial paint and repurposed as his own art, or had a Coca-Cola logo painted on the side or deliberately dropped and broken in an act of inane iconoclasm staged for the camera in three parts — holding, releasing and smashing.

If you go to the show you’ll see representations of Ai’s ordeals at the hands of the Chinese authorities. A film features his studio, self-designed and constructed by his team of workers over a period of a year, a fairly impressivelarge work of architecture, destroyed by order of the same official body that invited him to build it in the first place.

And you can see him in detention in a secret prison, in the form of a series of models housed in large metal boxes. His few clothes are on wire hangers in an open cupboard, there’s a bare lightbulb, minimal objects in the room, and he is accompanied at every moment as he sleeps, eats, exercises, submits to interrogation by officials and uses the toilet, by two guards forbidden ever to communicate with him.

Who could cope with it, to be repeatedly told by officials over 81 days (the first 30 in handcuffs) that you’ll never get out, or it won’t be for at least 10 years; and always to be aware that in the eyes of your family you’ve simply disappeared (other artists detained at the same time are still held today)?

And yet these 3D tableaux don’t bear much examining. When he first showed the work in a church in Venice three years ago, surrounded by the church’s permanent adornments of religious art in the Baroque style, Ai’s overall title S.A.C.R.E.D. — each of the letters corresponds to one of the six boxes — suggested a spiritual journey. Further subtitles, Entropy, Doubt, Supper, Accusers, Cleansing and Ritual, suggest the life of Christ. Maybe a replica of the church interior should have been supplied for the RA.

Ironists sometimes have to suffer irony turning back on them, and it’s ironic that Ai should have earned the right to claim a genuine spiritual journey because of a testing that really happened, while the art that stands for it possesses all the intensity of a museum model for children

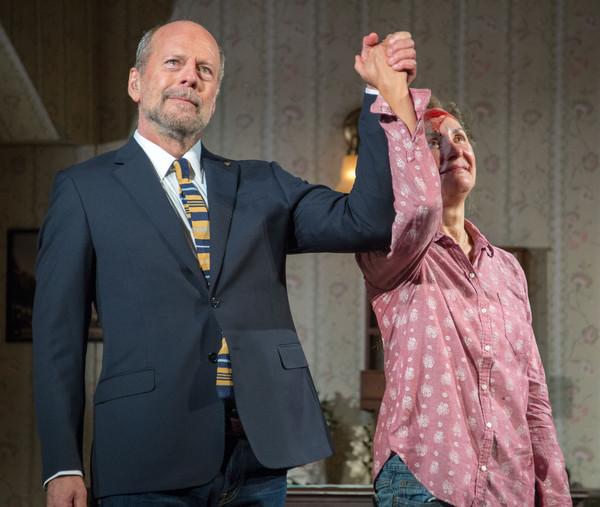

If you are in London , I would highly recommend you to visit Ai Weiwei’s exhibition at the Royal Academy it very impressing to see the truth…

Thanks for reading me

LenLenStyle

XOXO